John

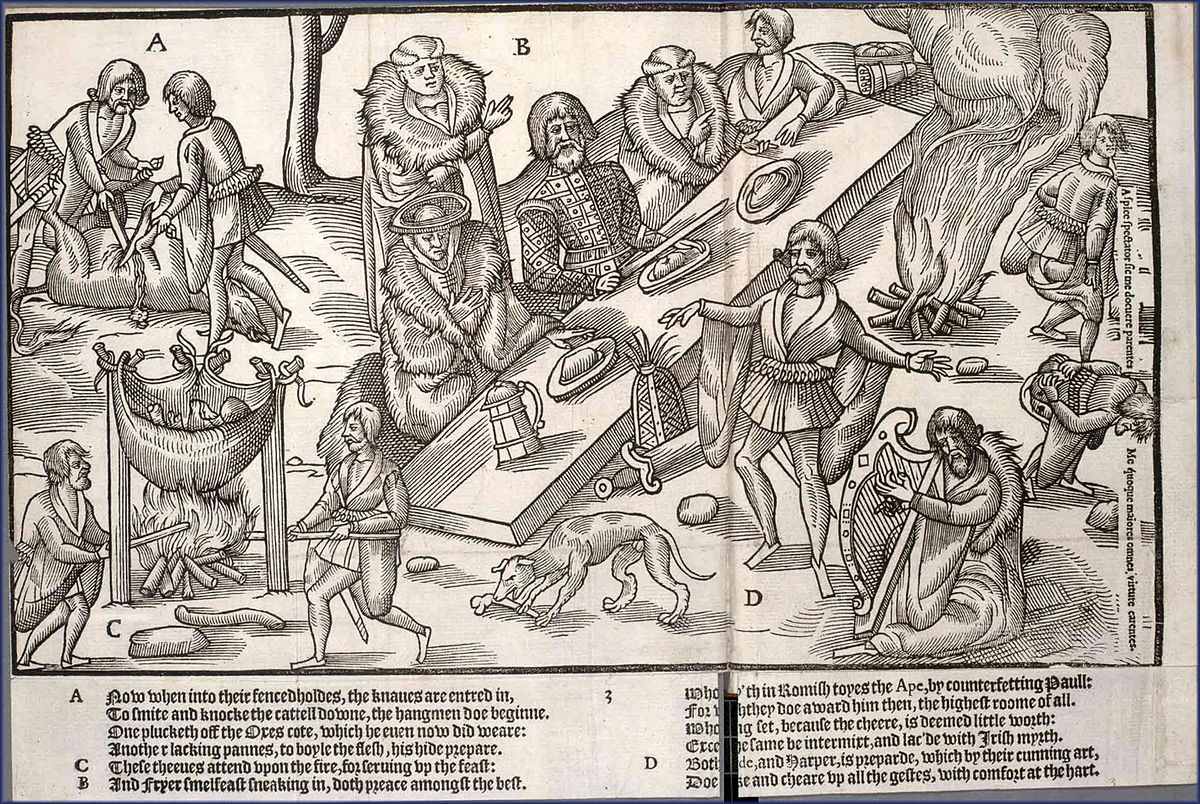

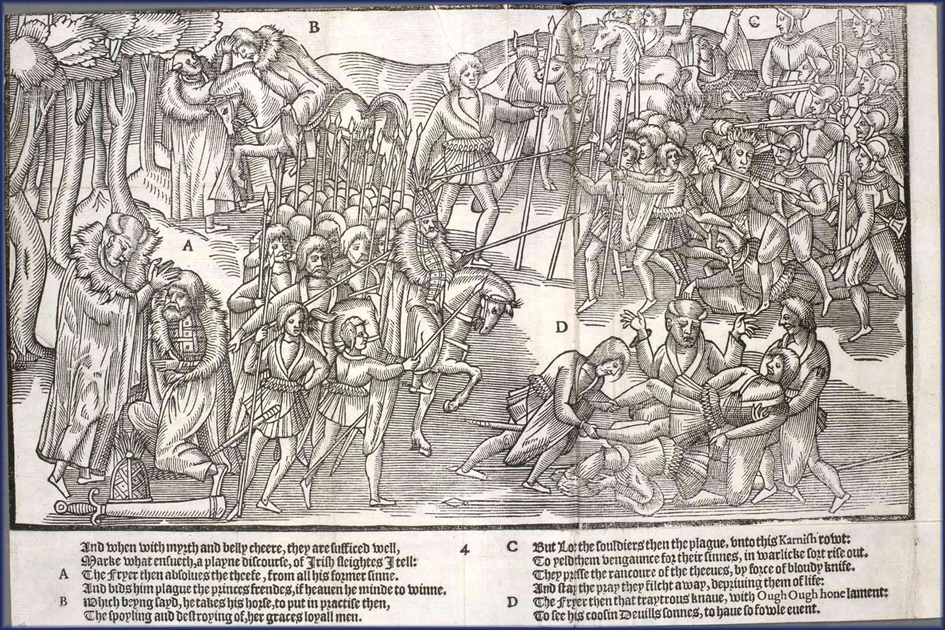

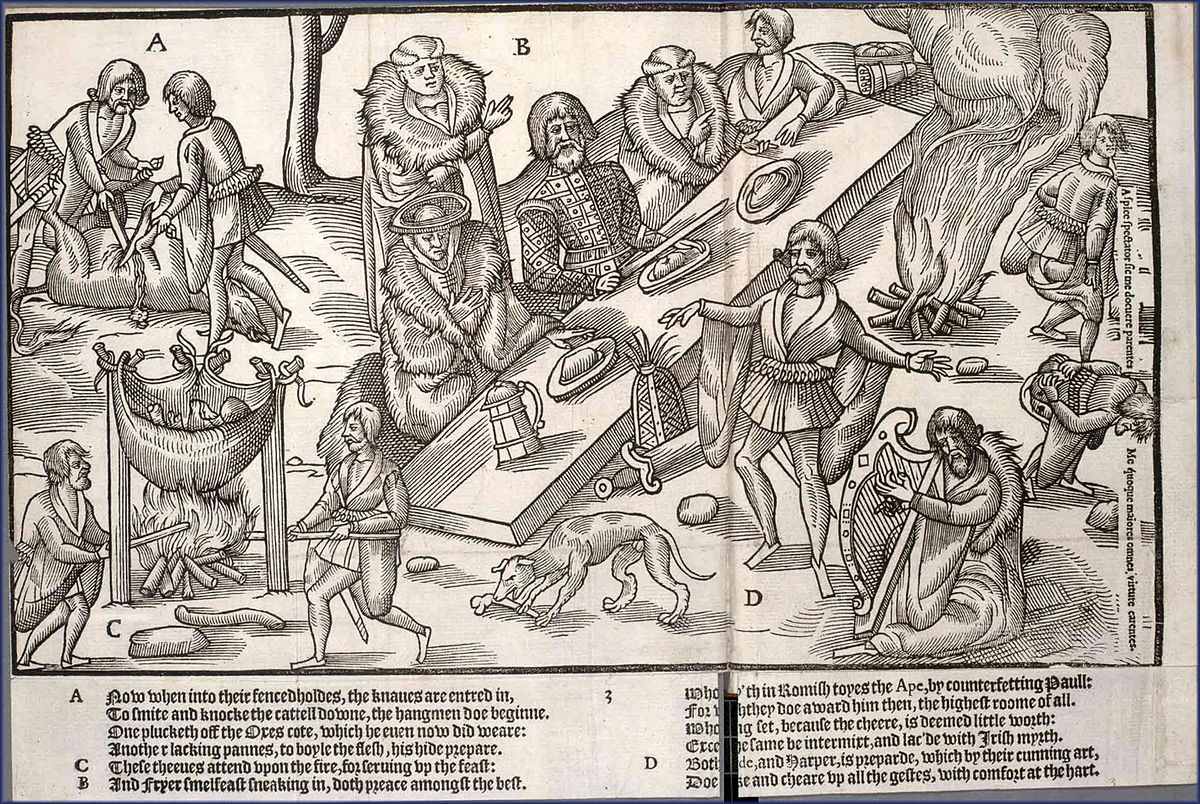

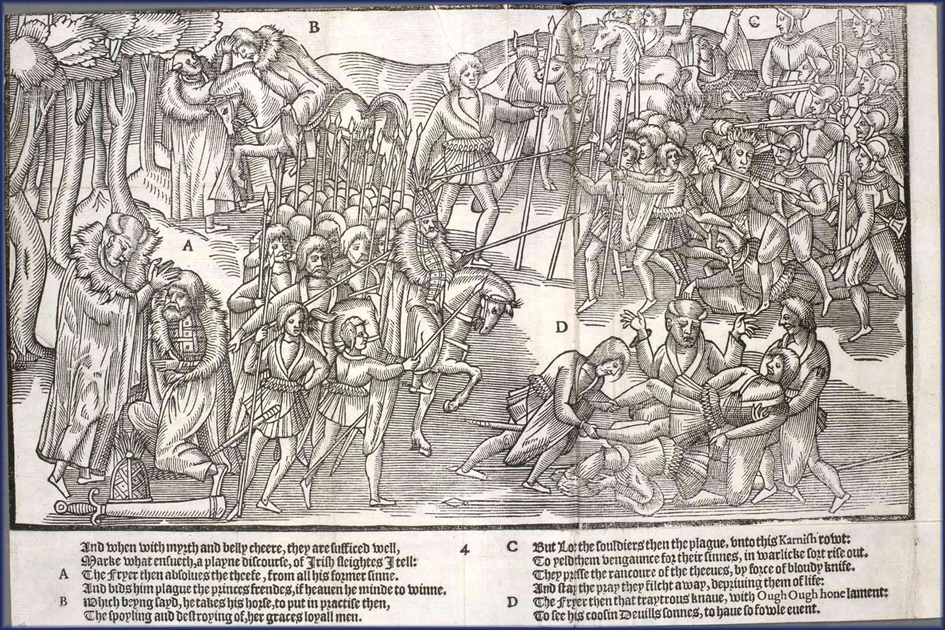

Derricke composed his work, The Image of

Irelande, with a Discoverie of Woodkarne [1], in 1578 - directly before the Baltinglass Rebellion in the Pale.

It includes a collection of 12 woodcuts and their accompanying verses. In these

woodcuts, Derricke addresses many aspects of Ireland’s culture and current

affairs as they stood before the rebellion, ranging from their dressing and

dining habits to the actions of Irish lords with and against the English.

Derricke’s attached artwork serves to reinforce his arguments regarding the

Irish in a visual manner. His third poem and plate combination, titled Kern Pillaging Their Own People on a Bodrag,

portrays Irish raiders as they pillage a settlement, indiscriminate of

ethnicity, and provides a commentary on the lifestyle and mindset of these

raiders. An Irish language work which counters this plate is the Irish poem

“Dia Libh” [2] written by

Aonghus Ó Dálaigh during the Baltinglass rebellion of 1580. In his work, Ó

Dálaigh praises the rebels for their bravery, identifies criticisms that they

have faced in the past, such as those made by Derricke, and encourages a

continuation of their course of action against the English. “Dia Libh”

adamantly rejects many of the implications of savagery and barbarousness that Kern Pillaging Their Own People on a Bodrag

touches upon, while also revisiting the negative connotation of some agreed

upon characteristics of the Irish, such as their aggressiveness. This can be

seen in the countering of the analogies Derricke uses, the reframing of the

impulsiveness depicted in Derricke as astounding bravery in “Dia Libh,” and the

introduction of religious imagery in “Dia Libh” as a means of justification for

some of the aggressive actions against the English as described in Derricke.

Derricke’s Kern Pillaging Their Own People on a Bodrag maintains a tone of

Giraldian-style criticism throughout in its use of subtle, biased descriptions

to lead to greater damaging implications regarding Irish culture. This can be

seen even from the initial lines when Derricke writes “here creeps out of Saint

Filcher’s den a pack of prowling mates, / most hurtful to the English Pale and

noisome to the states” (Lines 1-2). That is, a group of Irish raiders approach

a settlement of fellow Irishmen in a manner similar to that of a pack of

wolves. Furthermore, these Irish raiders are a constant nuisance not only to

the area with the greatest English authority, but also to Ireland as a whole.

The initial damaging implication of this is visible in his description of these

Irishmen as wolves, an animal notorious as a savage predator. The verse then

continues when Derricke writes “which spare no more their country birth than

those of th’English race” (Line 3). That is, that the Irish raiders treat their

own countrymen as they would an Englishman in their raiding. This portrayal of

the raiders as savages focuses on their lack of patriotism in their preying

upon fellow Irishmen. Derricke continues “they spoil and burn and bear away, as

fit occasions serve, / and think the greater ill they do, the greater praise

deserve” (Lines 5-6). That is, the raiders pillage whatever they can whenever

the opportunity is there. Having done this, they believe that their actions

deserve merit as opposed to punishment. This crushing accusation presented by

Derricke reinforces the Giraldian depiction of the Irish as quick tempered and

uncivilized, while also presenting the incurable trait of moral corruptness. He

further emphasizes this point when he writes “they pass not for the poor man’s

cry, nor yet respect his tears, / but rather joy to see the fire to flash about

his ears” (Lines 7-8). That is, these Irish raiders show no mercy to even the

weak and vulnerable while deriving pleasure from barbarously torturing their

victims. This depiction of their act as not only being merciless towards their

weakest victims but actually treating them more savagely is the ultimate

reinforcement of the view of the Irish as a savage and irreconcilable group.

Derricke continues in this manner until he ends the verse by writing “and thus

bereaving him of house, of cattle, and of store, / they do return back to the

wood, from which they came before” (Lines 11-12). That is, once these Irish

raiders are finished in the abuse and destruction of their victims, they return

back to the woods. This not only implies that the Irish raiders are living in

the woods like savages, but also that this chain of events is cyclical. What

follows from an understanding of these events as cyclical is an understanding

that these events must be stopped. Thus, we can see that Derricke uses his

description of this band of Irish raiders attacking a village as a way to

project a variety of irreconcilable traits onto the Irish nobility, their

soldiers, and perhaps even onto the Irish population as a whole.

In

“Dia libh,” Aonghus Ó Dálaigh addresses and responds to a lot of the

criticisms brought up by Derricke, while also encouraging and praising the Baltinglass

rebels who were fighting during this works composition. The difference in tone

can be seen immediately in the opening lines when he writes, “God be with you,

warriors of the Gaels! / Let no one accuse you of cowardice” (Lines 1-2). That

is, may God be on the side of the brave Irish soldiers in their battle. He

continues “you’ve never merited an insult / in times of battle or strife”

(Lines 3-4). That is, the Irish soldiers have been consistently brave in all

their actions. The poem continues in this manner of praise of the bravery and

ferocity of the Irish for several more lines. Ó Dálaigh then writes “If you

want to stake your claim to Ireland, / warriors of the valiant steps, / do not

shirk brave deed or combat / nor the frenzy of great battles” (Lines 9-12). That

is, in order for the Irish soldiers to be able to reclaim their lands, they

must not be wary of battle. This can be seen as an encouragement of those

participating in the Baltinglass rebellion to not shy away from the violence

necessary to regain control of their native lands. Ó Dálaigh continues from

this onwards with continuous alluding to the bravery of these rebels,

emphasizing their pride felt for the history and beauty of their native lands.

After many more religious and historical references, Ó Dálaigh then writes “it

kills me that foreigners are proclaiming as outcasts / the kings of Fodla and

their assemblies” (Lines 33-34). That is, it is upsetting to Ó Dálaigh that the

native nobility of Ireland are no longer recognized. He follows this up

immediately by writing “and that all they are now called in their homeland /

are shifty woodland bandits” (Lines 35-36). That is, the native nobility of

Ireland have fallen in the eyes of their own people from lords to raiders. This

is an important direct reference to Derricke’s writings in how it demonstrates

that the raiders that Derricke discusses could very well actually be native

lords. Again, Ó Dálaigh continues for many lines discussing the troubles facing

the native Irish lords but also remains optimistic and encouraging about the

Baltinglass rebels course of action. The poem comes to an end when Ó Dálaigh

returns to the same phrase as used in the beginning of the poem and writes “God

with them, sleeping and rising, strong men most valiant in battle; God with

them, waking and sleeping, and when the war is being waged” (Lines 57- 60).

That is, may God be on the side of the brave Baltinglass rebels in their

attempt to overthrow the English and regain control of their native lands. Thus,

we can see that this poem responds to Derricke by portraying the Irish in a

much more praiseworthy way in light of the Baltinglass rebellion while also

directly refuting several of Derricke’s claims.

The most obvious countering of Kern Pillaging Their Own People on a Bodrag

by “Dia Libh” can be seen in how the descriptions of the Irish used by Derricke

are revisited in “Dia Libh” in order to undermine or reframe them. The primary

example of “Dia Libh” reframing one of Derricke’s descriptions is visible in his

use of wolves to depict the Irish as savage predators as addressed earlier in

the discussion of the first line. The image of the Irish as wolves appears very

commonly in Giraldian texts as a vehicle utilized to emphasize the aggressive,

impulsive nature of the Irish. In “Dia Libh,” this imagery is also used, but

carries a different connotation, when Ó Dálaigh writes “wage war like valorous

wolves / you blessed band of shining arms / on behalf of your native land” (Lines

5-7). That is, may the Irish fight bravely and fearlessly for Ireland. This

quotation reinforces the comparison of the Irish with wolves but does so by

highlighting an alternative characteristic of wolves so as to reframe the

insult as praise. This reframing can be seen in the comparison of the Irish

with woodland bandits. Again, Derricke does not directly use this term in Kern Pillaging Their Own People on a Bodrag,

but after a long description of the Irish raiders pillaging a village, he

writes “they do return back to the wood, from whence they came before” (Line 13).

This comment is identified and responded to in Dia Libh, when O Dalaigh writes that it kills me “that all they

[the kings of Fodla] are now called in their homeland / are shifty woodland

bandits” (Lines 34-36). This reinforces the idea that the English describe the

lords as woodland bandits but also heavily implies that this is an unjust

description. By identifying the bandits described by Derricke as Irish

nobility, the story told by Derricke is undermined greatly due to his apparent

bias in his writing. Thus, while these may seem like very specific aspects of

Derricke’s writing to refute, by doing so Ó Dálaigh manages to undermine the

foundational facts that Derricke uses to emphasize the savage and barbarous

nature of the Irish nobility.

While Kern Pillaging Their Own People on a Bodrag depicts the Irish

nobility as a cowardly group who take advantage of the weak, the poem “Dia Libh” responds to this in

contradiction and is very much centered around the praiseworthy bravery and

martial ability of the Irish nobility. In Kern

Pillaging Their Own People on a Bodrag, a focus is placed on the effects of

the actions of the Irish through the distorted perspective of their alleged

victims. We can see this clearly in Derricke’s descriptions of the Irish

pillaging and unnecessary cruelty as discussed earlier. “Dia Libh” responds to this through its depiction of this

destructiveness in a very different light and its identification of ways in

which it can be channeled to free Ireland from English persecution. This

alternative perspective can be seen when Ó Dálaigh discusses the necessity of

bravery for the Irish when he writes

“If you

want to stake your claim to Ireland,

Warriors

of the valiant steps,

Do not

shirk brave deed or combat,

Nor the

frenzy of great battles” (lines 9-16).

This entire stanza

reflects many of the characteristics that Derricke discusses but instead with a

positive perspective being placed on acts involving frenzy and violence. Thus,

we can see that the methods of praise vary greatly between the two poems and

the characteristics which are deemed praiseworthy are even more polarizing.

One last, subtle method used in “Dia

Libh” to counter the wrongdoing of

the Irish that is depicted in Kern

Pillaging Their Own People on a Bodrag is an association with God.

Throughout “Dia Libh,” God is mentioned frequently, mostly regarding to him

being on the side of the Irish in this conflict. This can be seen even in the

very first line of “Dia Libh”. The role of God in this conflict is an important

one as a differing religion is one of the foundational points of contention

between the English and the Irish. By calling upon God, it demonstrates the

Irish’s confidence in their religion, and by extension their culture. Derricke

fails to portray this in his own work through his lack of references to

Protestantism. However, this association with God is confusing as much of what the

Irish are as described doing, both by Ó Dálaigh and Derricke, is egregiously

sinful. For example, in Derricke’s work when he writes “They pass not for the

poor man’s cry, nor yet respect his tears / but rather joy to see the fire to

flash about his ears” (Lines 7-8). This clearly depicts a lack of empathy

towards the poor and the committing of mortal sins by the Irish, which

undermines any religious association that Ó Dálaigh is trying to reinforce.

However, Ó Dálaigh could be implying that, despite the violent nature of the

Irish, God is on their side as the English deserve to be punished. This not

only demonstrates the superiority of the Irish and Catholicism in the eyes of

God, but also justifies the killing of the English and their expulsion from

Ireland. Thus, we can see that by incorporating God into the conflict, Ó

Dálaigh not only attacks the English religion, but also degrades them as worthy

of punishment in the eyes of God, a refreshing response to the Giraldian

perspective provided by Derricke.

Ultimately, “Dia Libh” takes a lot of the negatives attributed

to the Irish in Kern Pillaging Their Own

People on a Bodrag and reframes them in a positive light or refutes them

entirely. By understanding the time period and historical context in which

these two texts are written, it is easy to see that the Baltinglass rebellion

not only provides Ó Dálaigh with inspiration to respond to Derricke’s claims

about the Irish, but also provides him with evidence to the contrary. While the

most direct responses by Ó Dálaigh to Derricke can be seen in the addressing of

small details, such as the description of the Irish nobles as mere bandits,

once understood in their full capacity, these small argued-upon details serve

as the main foundation for the arguments that both side attempt to put forward.

Thus, we can see that through his response, Ó Dálaigh encourages the political

events going on during the point of time of his composition, while also using

them to frame a new understanding of the actions of the Irish in the past, and

ultimately to argue against Derricke’s biased depiction of Irish nobility.

Prints from John Derrick's "The Image of Irelande"

Comments

Post a Comment